Maori King Movement

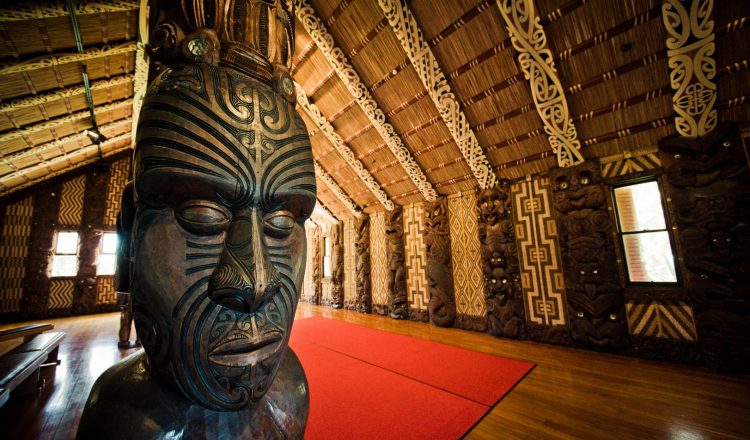

The first people to arrive on the shores of New Zealand were the ancestors of the Maori, somewhere between 1200 and 1300 AD. These skilled seafarers had used the wind, stars and currents to navigate their way from Polynesia and began to spread their influence around the island. The Maori people divided themselves into groups, known in their language as iwi. Iwi can translate to a nation or people, and these iwi were usually very large and had many sub-tribes within them known as hapu. The hapu is the primary unit within the Maori social structure and usually contains around 500 people, made up of many extended families. Each hapu is independent of the other hapu within the iwi and will usually have its settlement divided among the families.

As of a recent census, the largest iwi in New Zealand are:

- Ngapuhi (125,601)

- Ngati Porou (71,049)

- Ngai Tahu (54,819)

- Waikato (40,083)

The Maori Kings

At the top of the Maori social hierarchy was the chief. Each tribe had a chief that would listen to the concerns of their people and rally them in times of hardship. Despite settling lands, the tribes didn’t have a concept of land ownership. The land was only obtainable by conquest and only truly belonged to an iwi if they were actively using it. This became a major issue after the arrival of many European settlers, eager to buy their plot of land and establish towns and communities.

The Maori reaction to the European land grab was mixed, some iwi sold their territory, while others stood opposed to the intrusion. With the annexation of New Zealand by the British and the threat of military intervention, it fell upon Maori chiefs to act to try to preserve their home. They realised they couldn’t oppose the European advancement as divided iwi; instead, the Maori chiefs looked at what they perceived to be the strength of their opposition; a strong monarchy.

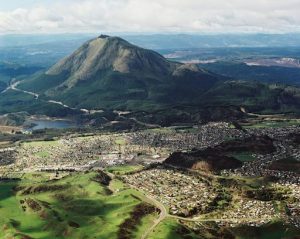

In 1858 the Maori selected the chief of the Waikato iwi as their king; Potatua Te Wherowhero. However, he died early into his reign and his son Tawhiao inherited the title and the struggle against the British. Disgruntled and concerned by the unification of the Maori, the British lead government invaded Waikato lands in 1863 and began the Waikato War that would end in the surrender of more lands to the British.

Over the next 100 years, a succession of Maori Kings would attempt to win back their lost lands on the political battlefield, keeping close ties with London and the British Crown. They were unsuccessful until 1975 when the first Maori queen, Queen Te Atairangikaahu came to a settlement with the government, a big step toward the progressive approach to Maori culture that we see today. She was the longest-serving Maori monarch, leading her people for 40 years until 2006 when her son, Tuheitia succeeded her. The Maori King continues to provide a cultural figurehead for the unified Maori and has an important ceremonial role.