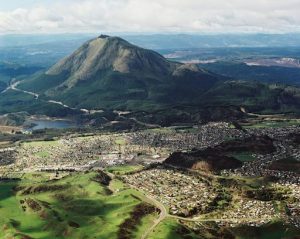

In New Zealand, supercritical geothermal research is focused on the Taupō Volcanic Zone – the area between Lake Taupō and Kawerau.

Chambefort said the newly-funded programme did not support any drilling during its five-year duration, although other initiatives were looking into options for drilling deep wells in the Taupō zone.

“We are hoping that five years after the end of the programme (in a decade), there will be a successful deep well in the Waikato or Bay of Plenty regions. The purpose of such a well would be to test existing scientific models and make adjustments as required,” she said.

So far geothermal wells in New Zealand had tended to be 1.5-3km deep. The supercritical fluids were likely to be found at depths greater than 4km.

“Our aim is to explore where in New Zealand could the best future targets be and to understand, using laboratory simulation, how these very hot fluids react with the rock, and how their use will affect deep reservoirs, and neighbouring shallower reservoirs, into the future,” Chambefort said.

“We see a compelling case for tapping into deeper and hotter geothermal resources to increase the overall contribution of geothermal.”

About 17 per cent of New Zealand’s electricity came from geothermal now, with as much electricity generated from geothermal as from fossil fuel in 2018.

While it could be said that the natural heat flux of the Earth could potentially be transferred as energy in any environment, volcanic provinces such as Taupō had a greater geothermal gradient, “which means we don’t have to drill to 10km to reach temperatures above 400C”.

“These very hot temperatures are closer to the surface than in some other countries, giving New Zealand a natural advantage,” Chambefort said.

A key aspect was to find permeability – rocks that hot fluids could pass through relatively easily. “It is one thing to have heat, but if no fluid can circulate through the rocks we cannot harvest this heat efficiently to the surface. Water is the main carrier for heat.”

The work being done now built on decades of research and New Zealand expertise in geothermal use in the Taupō zone. While there were strong partnerships with geothermal teams overseas, discoveries in other countries could not simply be applied in New Zealand.

“The geology is different in New Zealand. We need to study our reservoirs and find where faults may be permeable at depths of 4-5km,” she said.

“We also need to simulate high temperature and pressure geothermal conditions in a laboratory before producing meaningful findings for New Zealand.”

New Zealand had the drilling capability but such drilling would be costly and there were uncertainties. Industry was looking to science to provide information that would reduce uncertainties and risks of exploration and development of deep geothermal resources, Chambefort said.

“Deep geothermal generation will only go ahead in New Zealand when there is confidence that it can be done safely and sustainably.”