Economic history

When Europeans started arriving in New Zealand, they encountered the native Maori people. Maori tribes made a living from agriculture, fishing, and hunting. Trade was conducted through a barter system, and there was no concept of currency or property rights for land.

Many of the first Europen settlers were involved in activities such as sealing, whaling and forestry, and they traded with the Maori for food and other services.

In 1840 the British Crown and several Iwi (Maori tribes) Maori signed the Treaty of Waitangi. It was around this time that the first wave of European settlers arrived in New Zealand.

Misinterpretation around the meaning of land ownership meant Maori sold their land within realising they were doing so. Tensions led to conflict which saw a series of land confiscations by the Crown.

Throughout the 1860s the Europen settler population grew, and Maori declined due to the import of European diseases, alcohol and weapons. The Maori population did not begin to recover until the twentieth century.

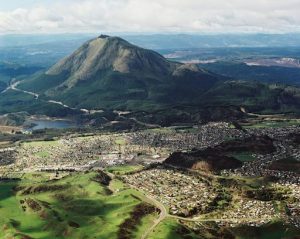

Also during the 1860s, gold was discovered in Thames and Otago, leading to a gold-rush. Around this time, sheep farming began in New Zealand. Demand for wool in the United Kingdom provided a significant boost to the New Zealand economy.

Economic relations between New Zealand and Britain continued to expand. With the introduction of refrigeration, New Zealand was able to supply foodstuffs to the United Kingdom. By 1914 New Zealand was one of the wealthiest if unequal countries in the world.

War

World War One disrupted agricultural production in Europe and increased demand for New Zealand products. Agriculture land rapidly increased in value, and an economic bubble developed, finally collapsing during the global economic downturn in 1929. Many industries relating to agriculture were affected, and New Zealand slipped into an economic depression.

The 1931 Napier Earthquake created a boost to the regional economy with investment into the reconstruction of the city. By 1932 the New Zealand government devalued the currency to make New Zealand products less expensive to European importers. Also in 1932, Britain and New Zealand signed the Ottawa Agreements on imperial trade which strengthened New Zealand’s position in the British market at the expense of non-empire competitors.

In 1935 the newly elected Labour Government nationalised the central bank (the Reserve Bank of New Zealand). The new government also created policies to support agricultural marketing, money lending and launched a state housing scheme.

Post War

New Zealand’s economy continued to struggle following the end of World War 2. By the 1960s the United Kingdom began moving away from its Commonwealth partners, including New Zealand and joined the Europen Economic Community.

The New Zealand government realised it needed to diversify its export markets and began negotiations with Austria. In 1965 the New Zealand – Australia Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed. The FTA was further upgraded in 1983 with the Closer Economic Relations (CER) agreement.

Between 1973 and 1984, New Zealand was overwhelmed by a series of inter-related economic crises and government mismanagement which created rising inflation and increasing unemployment.

Reform

Discontentment with the government saw a Labour government elected in 1984. Within weeks of taking office, the government undertook sweeping reforms to deregulate the economy.

The government removed controls on interest rates, opened up the financial markets and in 1985 floated the New Zealand dollar. To support trading, the government privatised trading organisations, reduced tariffs and removed import licensing.

The removal of credit controls led to increased private sector borrowing. Asset prices grew sharply, and the New Zealand economy expanded. Banks wanting greater profits lowered their thresholds for lending. In 1987 the sharemarket crash caused numerous defaults on repayments, and the banks scrambled to curb lending, including increasing interest rates and raising the threshold for lending.

From 1984 the New Zealand dollar appreciated, making New Zealand exports less competitive. The agriculture sector bore the brunt of these changes, with many farmers selling their farms and moving to the cities. Cheaper imports hurt New Zealand manufacturing. A global economic recession further hurt New Zealand.

Open Economy

Annual inflation was reduced to low single digits by the early nineties. Economic recovery began towards the end of 1991. With a brief interlude in 1998, strong growth persisted and by 2006 had become one of the longest and strongest growth periods the country had seen.

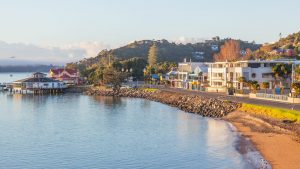

Famers began diversifying into cash crops such as grapes for wine. Manufacturing focused on increasing efficiency and exporting. There was a gradual shift towards a service economy, and tourism boomed as the relative cost of international travel fell.

While the 2008 Global Financial Crisis pushed New Zealand briefly into recession, the effects were minor compared to many other economies. Strong demand from China and Australia for New Zealand products kept the economy growing.