When does a language become extinct and when is it just dormant? This is a question that many linguists grapple with. Languages that no longer have native speakers, those who learned it as a child, are often considered “dead”. However, it’s not always that straightforward.

Take the Moriori language from the Chatham Islands, for instance. The last native speaker of Ta rē Moriori died in the early 20th century, but the language has a rich historical record and shares many similarities with te reo Māori.

This has sparked a project at the University of Auckland, in partnership with the Hokotehi Moriori Trust. The goal is to transcribe, translate and fully understand all existing texts of the Moriori language. The aim is to gain insights into the language’s grammatical properties and eventually produce a language grammar.

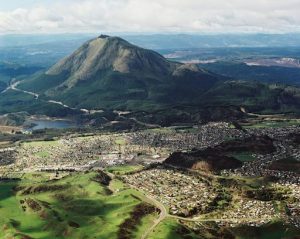

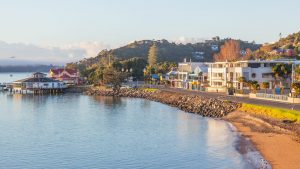

The Moriori people live on Rēkohu, or the Chatham Islands, about 800 kilometers off the east coast of New Zealand. They have a unique culture and language. However, the arrival of Europeans in the 1800s, followed by two Māori tribes from Aotearoa New Zealand, led to a rapid decline in the Moriori population and their language.

Despite this, the Moriori language has been preserved in various forms, making it an ideal candidate for language revival. This includes a small dictionary written in 1889, a set of short stories, and a 1862 petition from the Moriori to the New Zealand governor.

Reviving a language may seem ambitious, but it has been done before. The Wampanoag language from Massachusetts in the United States lost its last speaker in the 1890s. However, a significant archive of written literature, including government records and religious texts, was available. In the 1990s, a member of the Wampanoag community started analyzing these texts and was able to construct a dictionary and grammar. By 2014, there were 50 children considered to be fluent native speakers.

Sometimes, a “sleeping language” is a more accurate term for a language that is not currently being passed from generation to generation. The revived language will inevitably be slightly different from the original one. If adults were to learn the Moriori language from the texts, they could acquire a large number of words and grammatical structures. A child learning “new” Moriori from the adults would then instinctively fill in the gaps – most likely from other languages they hear, such as Māori or English.

So, Ta rē Moriori cannot be said to be dead or extinct, because there is a real possibility it can be heard again. Even now, Moriori words, phrases and songs are used around the Chatham Islands by Moriori themselves. It’s better to call it sleeping – and hope we can wake it one day.